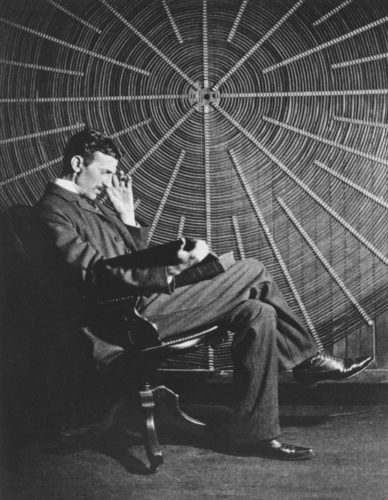

The entire universe fits on a blackboard in Oxford – sketched by Albert Einstein. The famous mathematician visited Oxford in 1931 and gave three lectures on his theory of relativity. The fact that the notes from his second lecture were preserved and nobody wiped them away is a sign of his high international reputation at the time. The tablet with his notes on the age, density and size of the universe is now in the History of Science Museum.

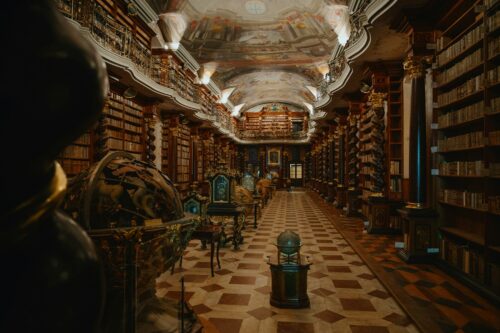

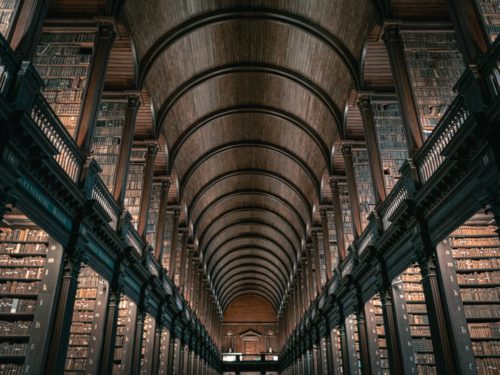

The museum itself is housed in the oldest surviving public museum building in the world: the Old Ashmolean in Broad Street. The building first opened its doors to the public in 1683 during the reign of Charles II – a controversial decision at a time when scientific and antiquarian knowledge in particular was reserved for the educated elite. Known at the time as the Ashmolean Museum, it initially housed the collection of the wealthy antiquarian Elias Ashmole. He acquired it from John Tradescant, who travelled the world collecting botanical, geological and zoological objects as well as man-made artefacts.

It was not until many years later that the History of Science Museum found its way into the historic building: founded in 1924, the museum was initially named the Lewis Evans Collection. As a graduate of Oxford University – also known as the Sundial Man – Lewis Evans worked with science historian Robert Gunther to establish the museum. Evans donated his collection of scientific instruments – including sundials in particular – and Gunther campaigned for their exhibition. Evans’ collecting career began when his father, the antiquarian and archaeologist Sir John Evans, gave him a sundial in the 1870s. Over the years, the Lewis Evans Collection expanded its range until the collection took on the name History of Science Museum in 1935.

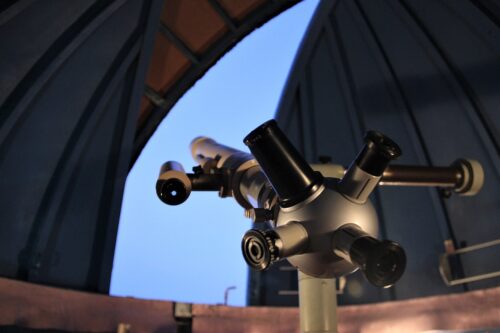

The public first caught a glimpse of the Collection 100 years ago. At that time, it mainly consisted of Evans sundials and other mathematical instruments such as astrolabes, which were used for various purposes such as timekeeping, celestial navigation and astrology. Today, visitors can view early astronomical and mathematical instruments from all over Europe and the Islamic world alongside Einstein’s table. A large collection of microscopes is also among the museum’s exhibits. There are also objects from the fields of chemistry, medicine and telecommunications, as well as portraits of scientists such as the Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius, who, among other things, founded the cartography of the moon, introduced new constellations and designed a star atlas. In total, there are 20,000 exhibits covering many aspects of the history of science from antiquity to modern times.

The museum can be visited free of charge and without registration. It is open Tuesday to Sunday between 12 noon and 5 pm.

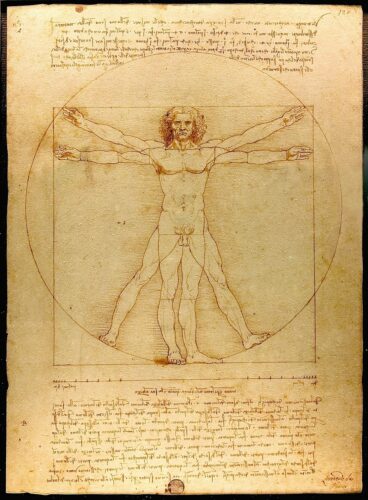

Photo: Sundial on a map; Credits: Pixabay/JaStra