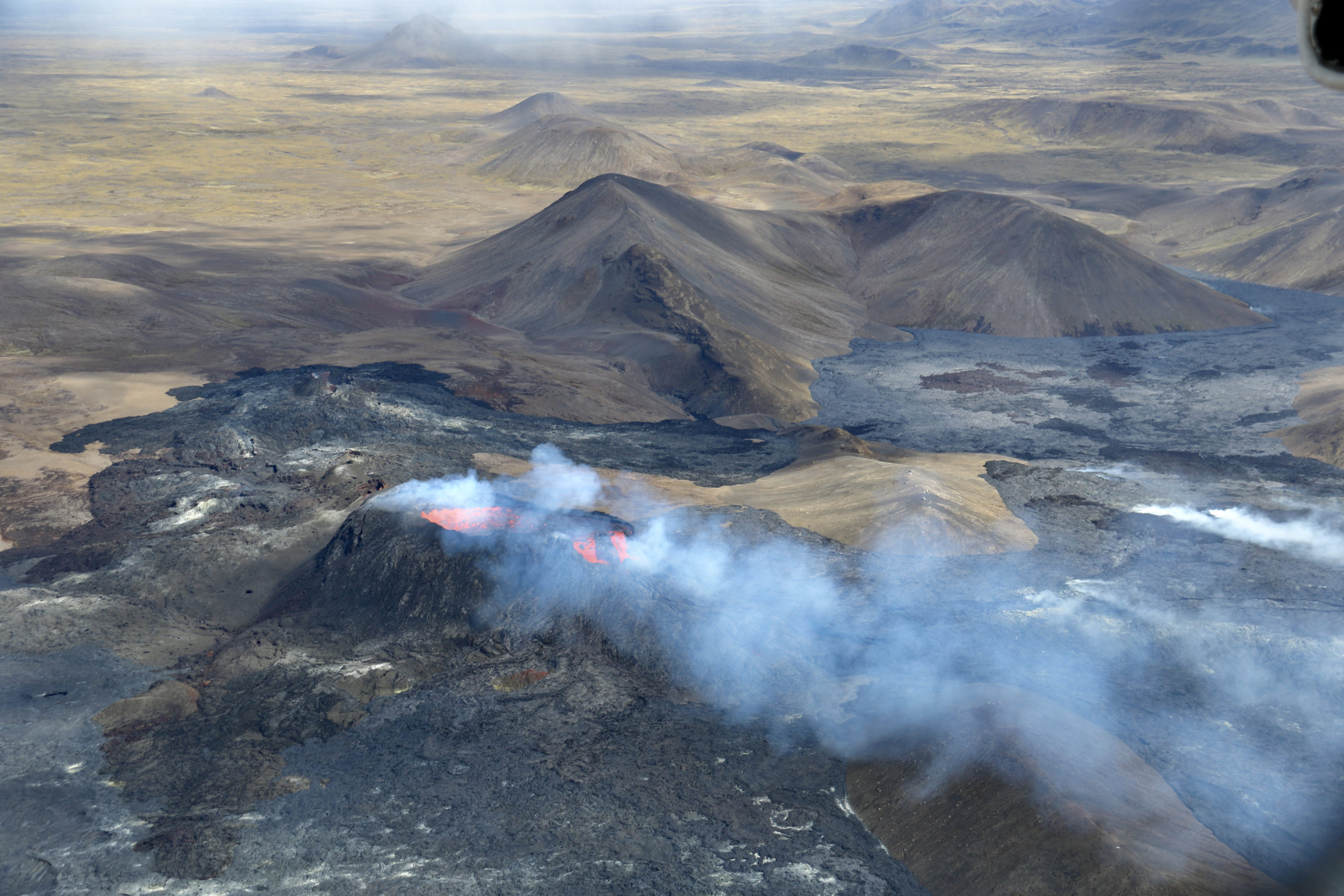

Mars is 56,000 kilometres away. But you don’t have to travel through space to explore it. A researcher takes us to Iceland’s volcanoes.

Photo: A splashing and bubbling volcano. Credit: Gro Pedersen

Gro Birkefeldt Møller Pedersen works where it gets dangerous. Her job is – literally – a dance on the volcano: Pedersen is a Danish geologist and researcher who analyses and maps volcanoes. She is currently working as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Iceland. She specialises in comparing the volcanic areas of Iceland with those on Mars.

Accordingly, 19 March 2021 was an exciting day for Gro Pedersen, because a volcano erupted just 30 kilometres from Iceland’s capital Reykjavík: The Fagradalsfjall volcano. The eruption took place in a valley called Geldingadalir on the Reykjanes peninsula in south-west Iceland. This eruption was something very special, says Pedersen: it had been the first time in about 800 years that a volcano has erupted in this region. Even now, the eruption continues (as of August 2021).

“The volcano is in the backyard of the capital. It is publicly accessible and also very accessible for scientists. By now, it is probably the best monitored eruption.”

Gro Birkefeldt Møller Pedersen, geologist at the University of Iceland

But it is not only the location of the volcano that is unusual: the eruption in Geldingadalir differs from many other volcanic eruptions in Iceland because it is particularly slow and steady – a rather unusual volcanic behaviour. “I like to compare volcanoes to people,” says the researcher: “They all behave differently.”

“I like to compare volcanoes to people. Each volcano is different, they all behave differently.”

Gro Pedersen, geologist

In the case of Fagradalsfjall volcano, the geological conditions are also special. There is no typical magma chamber under the volcano; the lava flows to the surface from an even deeper place than usual. Therefore, Pedersen’s task now is to learn as much as possible from this special eruption.

Expedition: Off to the volcanic landscape!

Gro Pedersen learns the most about volcanoes when she gets to know them personally, when she meets them on site. To do this, she undertakes expeditions into the volcanic landscapes, for which she has to prepare extensively. The Fagradalsfjall volcano is comparatively easy to reach, so the geologist usually only takes a GPS device and a camera there. Depending on the environment, however, she also needs protective clothing or is dependent on all-terrain vehicles; after all, there are also volcanoes in the Icelandic highlands or even on glaciers. For her work, Pedersen follows the lava outlines on site, photographs them and later compares them with the data from sensors. This provides insights into the eruption behaviour of the volcanoes.

These findings are important because they can improve the so-called basic modelling of lava. This means that it should be possible to better predict when and where moving lava flows will spread – and this for areas with volcanic activity worldwide. This can contribute to disaster control there.

Iceland is the largest volcanic island in the world

Iceland is the largest volcanic island in the world and does not bear the title “Land of Ice and Fire” for nothing: here glaciers meet magma. The competition between the elements played a major role in shaping the island. At the same time, Iceland is the youngest island in Europe: only 20 million years ago, volcanoes erupted along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean and formed the basis of the island. During the ice ages, masses of ice covered the island and continued to shape it. Its location on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is still the cause of volcanic activity today: the North American and Eurasian continental plates move apart by a few centimetres every year, causing magma from the earth’s interior to rise to the surface and change Iceland’s face again and again.

“In a way, you can research new land being born.”

Gro Pedersen

That is why Gro Pedersen’s research gives an insight into the island’s formation: “In a way, you can research how new land is formed,” says Pedersen. Not only on Iceland, but worldwide. According to Pedersen, that alone is reason enough to get excited about her findings.

Parallels with Mars

But the researchers from the fields of volcanology and astrobiology who are investigating the eruption in Geldingaladur are looking beyond Iceland and the Earth. They are looking into space, to Mars. For Mars is also known to be a volcanic planet, where liquid water is said to have existed many trillions of years ago. But when the planet cooled, most water evaporated or froze.

Hydrothermal systems as a possible habitat

Here, too, this interplay of fire and ice is interesting: when hot rock meets groundwater, so-called hydrothermal systems form. These are parts of the Earth’s crust in which there is a cycle of hot water and gases that can provide a habitat for microorganisms. Just like on Earth, such systems are also possible on Mars.

“Iceland provides a window into a certain environment you don’t see at many places.”

Gro Pedersen

While Mars has not offered any conditions for life on the surface for trillions of years, such subterranean hydrothermal systems could still have offered room for life. Researchers in volcanology and astrobiology are trying to find out whether and to what extent it is possible that such processes are still happening on Mars today by looking at terrestrial volcanoes, including the Fagradalsfjall volcano on Iceland.

A bus tour to the lava flow

t is doubtful that the many tourists will recognise this parallel to Mars. The eruption of Fagradalsfjall is fascinating enough in itself to attract thousands to the edge of the lava flows. This has led to a total of almost 100,000 people visiting the Geldingadalir volcano in the first few months, says Pedersen. And that in a country with a population of just over 350,000. One reason is that it is easy to reach: within a few minutes by car from Reykjavík, you can park your car and see the lava right away.

There are hardly any bans on entering. The Icelandic government focuses primarily on education and information. Pedersen recommends that visitors check regularly on the internet or with tourism companies. In bad weather or visibility conditions, it can be dangerous to be on site. Only a few areas are closed due to the danger of volcanic gases. Pedersen advises to have the wind at your back to prevent gas poisoning and to keep a safe distance from the lava, as it is constantly moving.

“Seeing a lava flow is a very educational thing to do.”

Gro Pedersen

With the right precautions, however, it is worthwhile to view this natural spectacle. According to Pedersen, anyone who wants to learn more about volcanic landforms should generally drive a lot through Iceland and look at different areas. After all, Iceland can give an insight into the interior of our world like hardly any other country on earth – and even views beyond our planet.